Let’s get one thing straight: a brainstorming session that ends with a team voting on their favorite ideas is not an innovation strategy. It’s a popularity contest. And it’s how you end up funding expensive, glittery distractions that go nowhere.

Most corporate innovation pipelines aren’t funnels; they’re sieves. They let everything through until the sheer weight of bad ideas collapses the entire structure. The goal of early-stage innovation isn’t to find the one good idea. It’s to kill the hundreds of bad ones as cheaply and quickly as possible.

The Cost of Indecision

Why is ruthless screening so critical? Because the cost of pursuing a bad idea isn’t just the money you burn developing it. It’s the opportunity cost. While your best engineers and marketers are tied up polishing a dud, your competitors are scaling the ugly-but-effective idea you discarded because it wasn’t sexy enough.

Consider the graveyard of well-funded failures.

Tata Motors launched the Nano in India, convinced a $2,500 car was a brilliant idea. They screened for price but not for safety or quality. The result? Cars that spontaneously combusted and a brand synonymous with “cheap and dangerous.” The idea wasn’t just bad; it was lethal to their reputation.

Amazon’s Fire Phone was a technologically sound device that screened perfectly within the company’s ecosystem. But they failed to screen for one critical factor: nobody outside the Amazon bubble wanted a phone that was primarily a shopping device. The project cost them a reported $170 million and was dead within a year.

Early screening saves you from yourself. It replaces gut feel, internal politics, and executive pet projects with a dose of market reality before you’ve spent a dime on development.

Stop Asking “Do You Like It?”

The most useless question in innovation is “Do you like this idea?” It invites bias, politeness, and outright lies. The right questions are about trade-offs.

This is the lesson Coca-Cola learned the hard way in 1985. Facing pressure from Pepsi, they conducted 200,000 blind taste tests. The data was clear: a new, sweeter formula—dubbed “New Coke”—was preferred over the original. Based on this screening, they launched the new product and, in a fatal move, discontinued the old one. The public outcry was immediate and visceral. Coke hadn’t just screened for taste; they should have screened for brand loyalty and the emotional connection people had to the original. They asked, “Do you like this new taste more?” when they should have asked, “Are you willing to give up your Coke for this?” The answer was a resounding no. They screened the product, but they failed to screen the business decision.

Modern screening platforms force these choices. Tools like Dig Insights’ Upsiide don’t just ask for opinions; they create a simulated market. They pit ideas and attributes against each other. Consumers vote with their attention and their (hypothetical) wallets. This approach, rooted in methodologies like conjoint analysis and MaxDiff, moves you from abstract preference to predicting market share.

It answers the real question: How does our idea stack up against your own products and the current market leaders?

This isn’t feedback. It’s decision-making data.

Add The Jobs-to-be-Done Litmus Test

Before you even get to sophisticated attribute testing, every idea must pass a simpler, more fundamental test: the Jobs-to-be-Done (JTBD) filter.

Ask your team:

- What specific “job” is the customer hiring this product to do? (e.g., “Help me feel more confident during my presentation,” not “A new presentation software.”)

- How are they getting that job done now? (Your real competitors are often weird workarounds, not other products.)

- Is our solution MUCH better than the current way?

If you can’t answer these questions with brutal clarity, the idea is not ready for screening. It’s not even an idea yet. It’s a wish.

Once you have JTBD clarity, and you know how your ideas stacks-up against real-world products, you can map ideas on a simple Desirability/Viability Matrix.

Desirability/Viability Matrix.

Desirability (Does the customer want it?) and Viability (Can we make money from it?) are the only two axes that matter at this stage.

Feasibility (Can we build it?) is a later-stage problem. If nobody wants it or it can’t make money, it doesn’t matter if you can build it.

The Enemy Within: Your Own Bias

The biggest threat to effective screening isn’t a lack of data; it’s the biases that prevent you from hearing what the data is telling you.

- Confirmation Bias: You look for data that supports your pet idea and dismiss anything that contradicts it.

- Innovator’s Bias: You’re so in love with your solution that you can’t objectively see its flaws.

- “Expert” Bias: The highest-paid person’s opinion carries more weight than the data.

How to counter this? Structure.

- Set Kill Criteria in Advance: Before you see the results, agree on what constitutes failure. (e.g., “If the idea doesn’t score in the top 20% against the benchmark, we kill it.”) This prevents you from moving the goalposts emotionally.

- Anonymize the Ideas: Strip away the names of the people who proposed them. Judge the idea, not its author.

- Appoint a Devil’s Advocate: Designate one person in the room whose only job is to argue against every idea, using the data to make their case.

The Screening Funnel

Don’t think of screening as a single event.

- Strategic Fit. Does this align with our business strategy and brand? Is the market big enough to matter? (A simple checklist).

- Quantitative Screening. Run the surviving ideas through a platform like Upsiide. Get hard data on consumer appeal and market potential. (Data-driven triage).

- Qualitative Validation. Take the top 3-5 ideas and explore the “why” behind the numbers with in-depth customer interviews. (Concept refinement).

Your goal is to have no more than a handful of ideas emerge from this process. If you have ten “winners,” your filters aren’t tight enough.

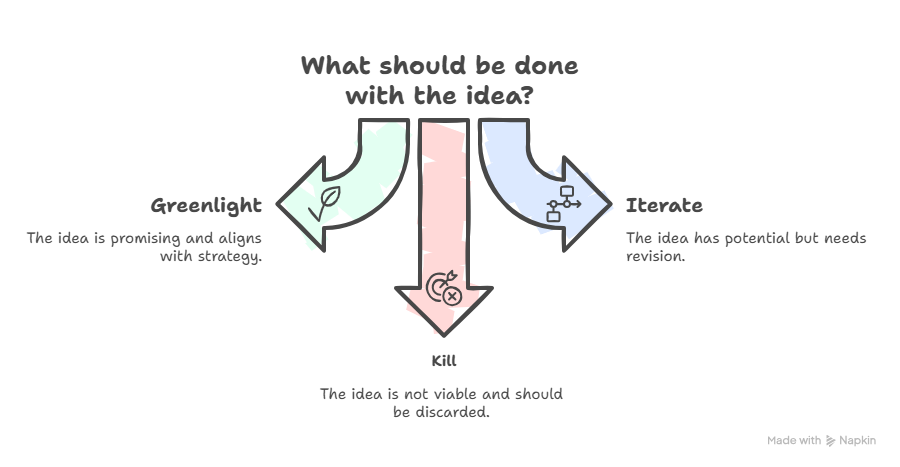

Greenlight, Iterate, or Kill

The output of any screening process is a decision. Not a “let’s discuss this more,” but a firm call:

- Greenlight: The data is unambiguous. The idea solves a clear job, has strong consumer appeal, and aligns with our strategy. Time to build a MVP/ MCV.

- Iterate: The core concept is promising, but a key attribute or the core message is wrong. Send it back for a specific, targeted revision and re-screen.

- Kill: The idea is a solution in search of a problem, has no market appeal, or is strategically irrelevant. Kill it. Celebrate the kill.

Every idea you kill frees up resources for one that might actually work.

In the early 2000s, Procter & Gamble faced a hard truth: only 15% of their innovations were hitting their targets. They were a sieve. By implementing a disciplined screening process, they tripled their innovation success rate.

They didn’t get more creative; they got more ruthless. They celebrated the projects they killed, knowing that each one was a victory for focus and a step toward a real breakthrough.

Most organizations are good at greenlighting and terrible at killing. The best innovators are the most ruthless executioners.